Bir çevrimiçi yayın olan “Türk Dillerinin Kendi İçinde Sınıflandırması ve Türk Dillerinin Göçü” (The Internal Classification & Migration of Turkic languages) konulu çalışmanın 8.1 sürümünün yer aldığı site (scienceontheweb.net) kapandığı için bu değerli çalışmanın araştırmacılara faydalı olması, kaynaklık etmesi amacıyla arrchive.org'dan (Internet Arşivi, 349 milyar arşivlenmiş web sayfasının yanı sıra kitaplara, filmlere ve müziklere ücretsiz evrensel erişim sunan, kar amacı gütmeyen bir dijital kütüphanedir.) ulaşılarak yeniden düzenlemiş ve paylaşılmıştır.

Çalışmanın ilk 20 sayfası burada metin olarak paylaşılmıştır. Tamamını (225 sayfa pdf.) sayfa sonunda bulunan bağlantı aracılığı ile indirebilirsiniz.

THE TURKIC LANGUAGES IN A NUTSHELL

The Internal Classification & Migration of Turkic languages

Version 8.1

v.1 (04/2009) (first online, phonological studies) > v.4.3 (12/2009) (major update, lexicostatistics added) > v.5.0 (11/2010) (major changes, the discussion of grammar added) > v.6.0 (11-12/2011) (major corrections to the text; maps, illustrations, references added) > v.7.0 (02-04/2012) (corrections to Yakutic, Kimak, the lexicostatistical part; the chapter on Turkic Urheimat was transferred into a separate article; grammatical and logical corrections) > v.8 (01/2013) (grammatical corrections to increase logical consistency and readability, additions to the chapter on Uzbek-Uyghur, Yugur)

Abstract

The internal classification of the Turkic languages has been rebuilt from scratch based upon the phonological, grammatical, lexical, geographical and historical evidence. The resulting linguistic phylogeny is largely consistent with the most prevalent taxonomic systems but contains many novel points.

Contents

1. Introduction

1.1 Preliminary notes on the reconstruction of Proto-Turkic

2. Collecting factual material

2.1 An overview of the lexicostatistical research in Turkic languages

2.2 Dissimilar basic lexemes in the Turkic languages

2.3 The comparison of phonological and grammatical features

3. Making Taxonomic Conclusions

Bulgaric

Some of the exclusive Bulgaric features

Yakutic

Where does Sakha actually belong?

How did Sakha actually get there?

On the origins of Turkic ethnonymy

Altay-Sayan

Tofa and Soyot closely related to Tuva

The Khakas languages

Khakas and Tuvan share no exclusive innovations

Altay, Khakas and Tuvan form the Altay-Sayan subgroup

Great-Steppe

Kimak-Kypchak-Tatar, Kyrgyz-Kazakh, and Chagatai-Uzbek-Uyghur seem to form a genetic unity

Great-Steppe and Altay-Sayan seem to be closer to each other than to Oghuz-Seljuk

Kyrgyz-Chagatai

Kazakh is closely related to Kyrgyz

Altay-Kyrgyz isolexemes

Chagatai looks like Karakhanid affected by Kyrgyz

Kimak-Kypchak-Tatar

The Kimak subtaxon

The relationship between Oghuz and Kimak

On the origins of the ethnonym Tatar

Bashkir is closely related to Kazan Tatar

On the origins of Nogai

Karachay-Balkar, an atypical Kimak language

Oghuz-Seljuk

Oghuz is still a valid subtaxon

Seljuk as a subtaxon of Oghuz

Oghuz-Seljuk is indirectly related to Orkhon-Karakhanid

Notes on the confusion about y-/j- in Oghuz and Kimak

Orkhon-Karakhanid

Orkhon-Karakhanid as a valid subtaxon

Khalaj is probably an offshoot of South Karakhanid

Yugur-Salar

Yugur seems to be ancient

Salar has little to do with Oghuz, but quite a lot with Yugur and Uyghur

4. The Resulting Internal Classification of Bulgaro-Turkic languages

4.1 The Genealogical Classification of Bulgaro-Turkic languages

4.2 The taxonomic Classification of Bulgaro-Turkic languages

4.3 The Geographical Tree of Bulgaro-Turkic languages

5. References and sources

Introduction

The present study of the Turkic languages (2009-2012) was started as brief online notes that gradually grew into a series of online publications. The study is mostly an original research with relatively few references to previous theories. Most analysis was based upon factual evidence collected from dictionaries, grammars, language textbooks, native speakers on the web, sound and video fragments, books and articles containing detailed descriptions of specific languages. The resulting conclusions rarely draw from historically accepted opinions or assumptions produced by other researchers, rather attempting to build a logically consistent view of the spread of Turkic languages and their internal classification grounded in the nearly independent and relatively comprehensive step-by-step analysis.

Nevertheless, the author deeply appreciates the extensive input from people who worked on the vast amount of Turkological literature dedicated to the numerous Turkic languages, as well as those who helped directly or indirectly by providing corrections and valuable notes by email or through web forums, without whose interest and collaboration this work would never have come to life.

The present article provides all the linguistic argumentation concerning the internal classification of Bulgaro-Turkic languages. Furthermore, there are three other separate articles which can be regarded as part of the same work.

The Lexicostatistics and Glottochronology of the Turkic languages (2009-2012) is a detailed research of Swasdesh-210 wordlists, which dates the Turkic Proper split to about 300-400 BC, and the Bulgaro-Turkic split to about 1000 BC.

The Proto-Turkic Urheimat & The Early Migrations of the Turkic Peoples (2012-13) is a detailed analysis of the early Bulgaro-Turkic migrations largely based upon the results obtained in the glottochronological analysis above and the present classification. The Proto-Turkic Proper Urheimat area was positioned northwest of the Altai Mountains, and the earlier Proto-Bulgaro-Turkic Urheimat in northern Kazakhstan. The work explores the associations with the major archaeological cultures of the Bronze and Iron Age period in West Siberia.

The Turkic languages in a Nutshell (2009-2012) embraces the final classification, trying to focus on the most well-established conclusions from various works including the present investigation. It also contains multiple illustrations, notes on history, ethnography, geography and the most typical linguistic features, which essentially makes it a basic introduction into Turkology for beginners.

1.1 Preliminary notes on the reconstruction of Proto-Turkic

Before we proceed with the main analysis, let us consider the reconstruction of the Proto-Bulgaro-Turkic word-initial *j/*y, which has become a long-standing issue in Turkological studies, and which may affect certain conclusions in the main part of this publication.

Many proto-language reconstructions in various branches of historical linguistics are often based entirely on the supposed readings of the ancient texts from the oldest family representatives. For instances, in the Indo-European studies we can avail ourselves of the wonderful attestations of Ancient Greek, Latin and Avestan. However, when the oldest representatives are poorly read and interpreted, such an approach can result in errors.

Generally speaking, an ancient extinct language can only be seen suitable for reconstruction purposes, only if it meets several conditions, namely: (1) it is a uniquely preserved language closely related to a proto-state without the existence of any alternative sibling branches; (2) it is so well-attested that its data are completely reliable and no significant misinterpretations can occur from occasional mistakes in ancient writing, reading (e.g., from abraded petroglyphs), copying of the material, translation, interpretation, etc; (3) the scriptclosely and adequately reflects the original pronunciation and we know full well how to correctly reconstruct that pronunciation from that script; (4) the linguistic material should should be dialectically uniform, in other word it should constitute just one language, not a mixture of various dialects or languages gathered by numerous contributors during generally unknown periods or from unknown areas [which is referred herein as the Sanskrit dictionary syndrome].

Obviously, the situation in Turkology does not meet these criteria. Orkhon Old Turkic, the oldest Turkic language attested in the inscriptions from Mongolia, fails to meet the first point (see details below), it barely gets in with the second one, and raises many objections with the third one. In other words, Orkhon Old Turkic may just be insufficiently old or much too geographically off-centered to be considered close enough to the proto-state. Moreover, there may be just not enough correctly interpeted material for the solid attestation and interpretation of ancient phonology. Orkhon Old Turkic is not as well reconstructed as, say, Latin and Greek in the Indo-European studies, so many readings are quite ambiguous. And finally, it often gets mixed in literature with Old Karakhanid, Old Uyghur and generally unknown Old Yenisei Kyrgyz dialects (given that not all of the Old Turkic inscription were made in Mongolia). Therefore one should not confuse the methodological basis established for the Indo-European reconstruction with the methods convenient for other language branches, such as Turkic. An old language is not always just good enough.

As a result, the reconstruction of Proto-Turkic should be conducted by means of a completely different approach, namely using materials from the well-attested modern representativesof Turkic languages. In that case, we should build a reconstruction using a lineal formula with separately determined lineal coefficients representing contributions for each particular language branch. This method is drastically different from the old-fashioned old-language-for-all model. As an example, when reconstructing Bulgaro-Turkic, we could roughly assign about 50% to Chuvash and about 50% to Proto-Turkic Proper, and then more or less equally divide the second half among the most archaic representatives from the main branches, e.g. (1) Proto-Sakha, (2) Proto-Altay-Sayan + Proto-Great-Steppe, and (3) Proto-Oghuz-Orkhon-Karakhanid , hence each one of the main Turkic branches would receive only about 50% /3 = 17% (see the classification dendrogram at the end of this article).

This example has been provided as a first-approximation approach to address the potential Old-Turkic-centristic attitude, which supposedly claims that "nothing that's not in Old Turkic could exist in Proto-Turkic" or that "Old Turkic is an ancient language, therefore it is more suitable for historical reconstruction". By contrast, the current revised method requires that Gökturk Old Turkic be considered as just one of several early Turkic branches, and it is hardly any more important for reconstruction purposes than about 17% or less.

However, the figures for the lineal coefficients depend on the genealogical topology of the most basic shoots in the internal classification dendrogram. Therefore, using Turkic languages as an example, we come to a general conclusion that a consistent internal tree-like language group classification must be built before proceeding with the reconstrution of a proto-language. In other words, an internal classification should be constructed prior to further linguistic or geomigrational analysis.

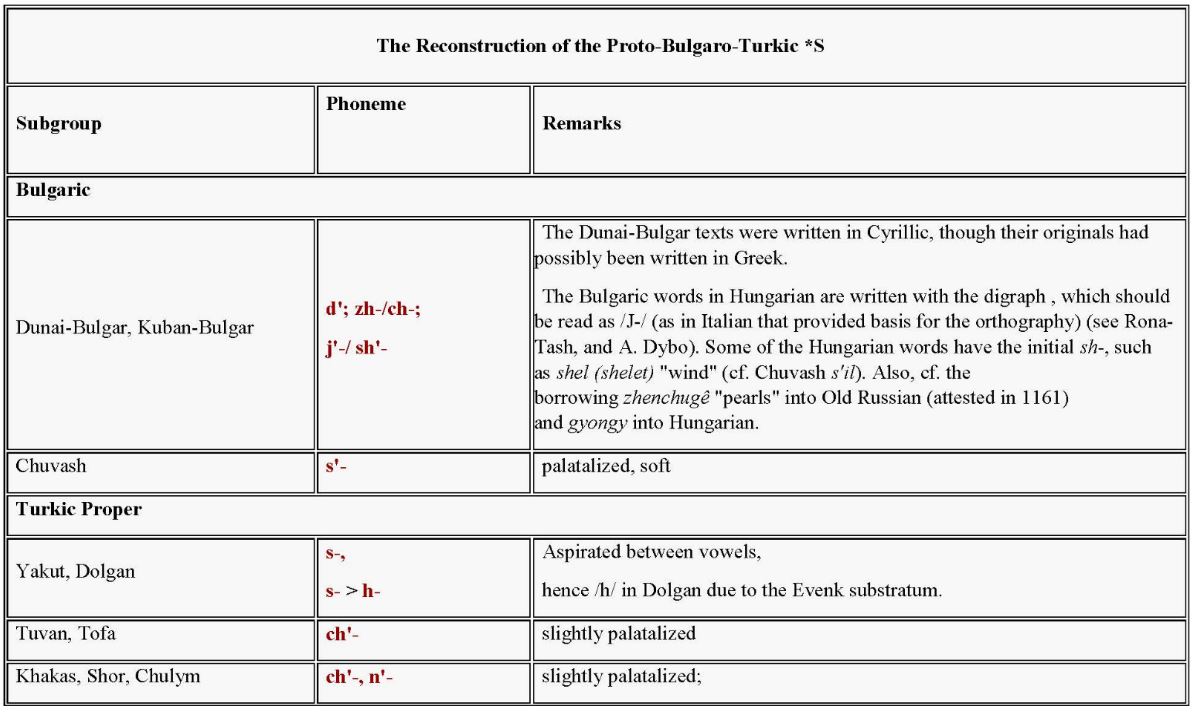

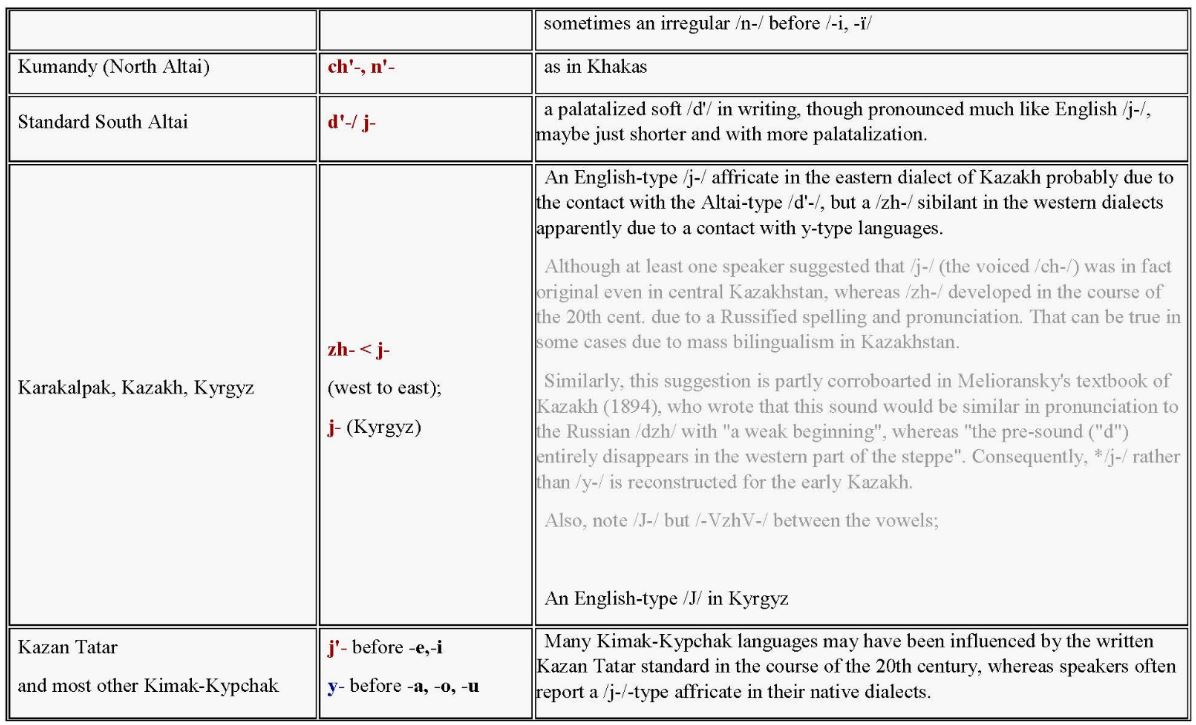

An example from the Revised Model: the reconstruction of the Proto-Bulgaro-Turkic *S-

The above reasoning can be exemplified by the following reconstruction of the Proto-Bulgaro-Turkic *S- (the S-symbol should be seen herein as just an arbitrary way to designate the *y-/ *j-phoneme as in Turkic yer / jer "place, earth", yol /jol "way", etc ). A very common error resulting from the Turkish-for-all or Karakhanid-for-all model is the conclusion that the words with the y- were pronounced exactly the same way in Proto-Bulgaro-Turkic. This idea is very common even among Turkologists outside Turkey, and seems to go as far back as the Mahmud al-Kashgari's classical Compendium of the Turkic languages (1073).

Note: Before proceeding with the further argumentation, we should confine ourselves only to the material internal to the Turkic languages, the Altaic and Nostratic languages being a completely separate issue that cannot be regarded herein at any length. This method can generally be called as an internally-based reconstruction vs. full reconstruction.

Note: We try to consistently use the Anglophone-based transcription throughout all the articles as opposed to the German-based transciption that goes back to the 19th century's tradition, therefore /y-/ denotes a semivowel as in "year" and /j-/ or /J-/ an affricate as in "Jack". To avoid occasional confusion, the capital denotation /J-/ has been used in some places for additional emphasis. The digraph /zh/ or monograph /ž/ are approximately similar to the voiced sibilant in French "je" or English "pleasure", "treasure". The use of complex UTF signs was avoided for reasons of readability and technical compatibility. For further details on transcription see The Turkic languages in a Nutshell.

The following table summerizes the pronunciation of the Turkic *S- in the most important branches:

This table shows that the pure /y-/ pronunciation is attested only within the following subtaxa:

(1) in the languages historically connected with the Orkhon-Karakhanid and Oghuz-Seljuk subgroups, even though there seems to exist some /y-/-to-/j-/ allophonic distribution in Uyghur, some Uzbek dialects and some Oghuz dialects;

(2) partly, in Yugur and Salar, which also belong to the southern Orkhon-Karakhanid habitat and may have been contaminated by it, considering they are located along the Silk Road outposts, where migrations were a very common phenomenon.

(3) partly, in the /ya-/, /yu-/, /yo-/ syllables, in the languages descending from the late expansion of the Golden Horde, such as Kazan Tatar (but not the Kimak languages with an early separation, such as Karachay-Balkar). Nevertheless, even in Kazan Tatar, many speakers still report an allophonic distribution of this phoneme, therefore a clear-cut /y-/ exists mostly in the written standard, produced more or less artificially after the 1920's, as well as in the recently Russified speech, rather than in older dialects or geographically marginal languages, such as North Crimean Tatar, Eastern Bashkir, etc. Moreover, we still have /jil/, not /yil/ "wind" before a high vowel even in the standard Kazan Tatar.

Consequently, we may conclude:

(1) Only the languages related or adjacent to the Oghuz-Orkhon-Karakhanid branch seem to have a clear-cut historical attestation of the /y-/ semi-vowel, whereas the majority of other branches with an early separation and long isolation either get jumbled data or seem to be clearly going back to something like a strongly palatalized sibilant /s'-/, /j-/, /d'-/, /ch-/ or a similar consonant sound.

This provides a purely statistical argument for our conclusion: there are more separate language branches that originally had an /s'-/- or /j-/-type phoneme than those that finally developed the /y/-phoneme. To put it in other words, it is statistically implausible that the supposed /y-/ > /j-/ mutation would have occurred simultaneously and independently in so many separately existing archaic branches.

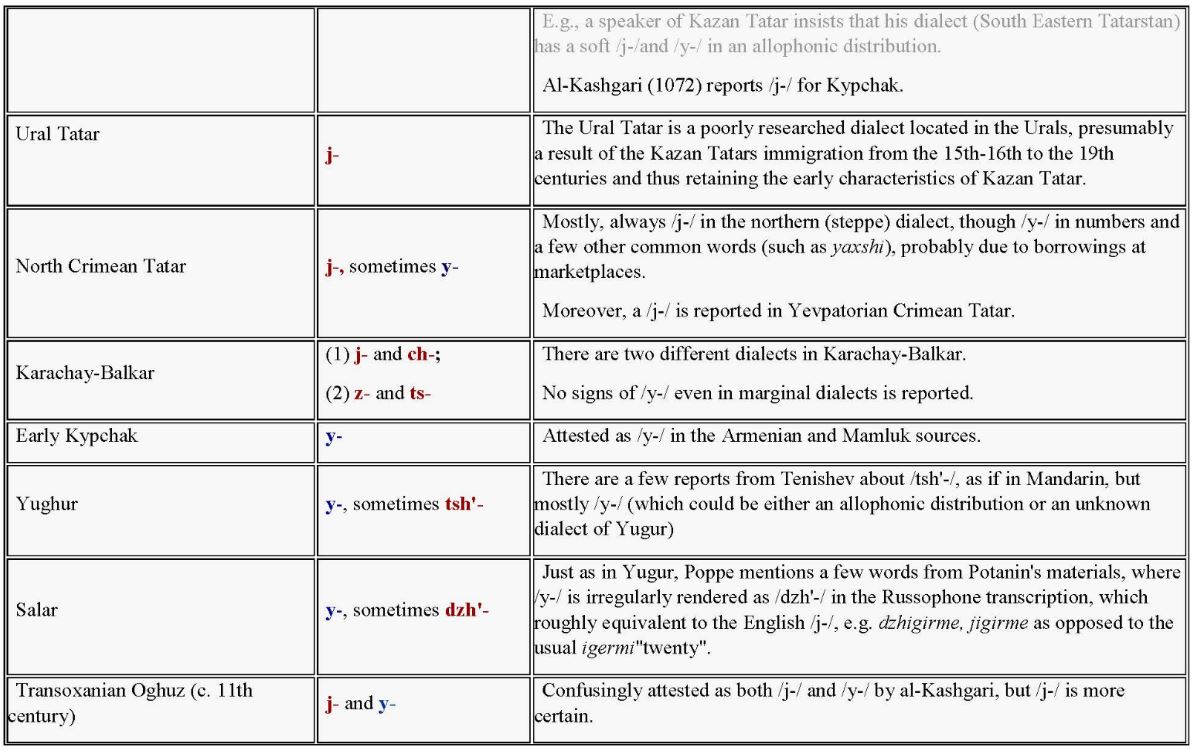

(2) As we can see in the fig. below, the distribution of the y-type phoneme seems to be located outside of the main historical diversification area of Turkic languages, therefore it appears to be a recent phonological mutation, apparently linked to the migration of the Orkhon-Karakhanid and Oghuz languages, which again implies that the development of /y/ might have been a rather unique phonological innovation in Orkhon-Karakhanid Old Turkic. This provides us with a second phono-geographical argument: only the J-type phoneme seems to be distributed near the putative homeland area of Turkic languages, not the y- semivowel.

As to the existence of the allophonic /y-/-to-/j-/ phonological variation in the Kimak-Kypchak-Tatar languages of the Golden Horde, such as Kazan Tatar, the existence of /y-/ may be explained as an early Oghuz influence. As we will show below, the Golden Horde languages and Oghuz share many linguistic features at several levels, therefore this type of borrowing is well corroborated by other evidence of mutual interaction.

(3) Moreover, if /y-/ were present in the proto-form, we would rather observe phonological variations of the semi-vowel /y-/ (not /J-/): e.g. we would find something like /y-/, /i-/, /0-/, /ê-/, /l'-/, /J-/, /zh-/ in the most archaic and diversified Siberian branches in the east (near the historical homeland of the Turkic languages), but what we do see in that area are the phonological variations of the palatalized consonant /s'-/: /s'-/, /s-/, /h-/, /ch'-/, /J-/, /zh-/, /d'-/, /ni-/, /y-/. On the other hand, the expected zero phoneme resulting from the loss of /y-/ is only present in the westernmost languages, such as Azeri (e.g. ulduz < yulduz "star", il < yil "year"), and, partly, in Turkish (cf. ïlïk, but Turkmen yïlï "warm"), which marks the /y-/-phoneme as a relatively recent and rather westernmost phenomenon connected with the spread of the Oghuz-Seljuk languages. This provides us with a phonological diversification argument: if the /y-/ semi-vowel were original, there would be a range of predictable sound changes in the most early diversified branches, but nothing of the kind is found there.

Therefore, from the evidence internal to the Turkic languages alone, we may conclude that the *S- proto-phoneme in question can be placed somewhere within the range of sibilants {/s'-/, /s-/, /h-/, /ch'-/, /J-/, /zh-/, /d'-/}, and it could not have been similar to the /y-/ semivowel as in modern Oghuz-Seljuk languages.

Actually, this conclusion concerning the reconstruction of the Proto-Turkic *S- is hardly novel and has been expounded several times by different authors, such as A.N. Bernshtam (1938), S.E. Malov (1952), N. A. Baskakov (1955), A.M. Scherbak (1970), as well as by the authors of the authoritative Russian publication, sometimes abbreviated as SIGTY, namelyin its volume [Pratyurkskiy yazyk-osnova. Kartina mira pratyurkskogo etnosa po dannym yazyka. (The Proto-Turkic language. The Worldview of the Proto-Turkic ethnicity based on the linguistic data.), Moscow (2006)].

Note: Generally speaking, SIGTY [Sravnintelno-istoricheskaya grammatka tyurkskikh yazykov ("The Comparative Historical Grammar of the Turkic languages")] is a large and verbose multi-volume Moscow compehensive publication with detailed cross-comparative analysis of morphology, syntax, vocabulary, semiotics and other aspects of Turkic languages, produced between the 1970's and the 2000's.

As an additional quite interesting argument, the authors of SIGTY suggest that, since other sonants, such as *r- and *l-, were absent or atypical in the word-initial position, there is no reason to believe that the /*y-/ semi-vowel, phonetically similar to a sonant, could be there either.

The opposite view, which mostly goes back to Radlov's work in the end of the 19th century is usually based on the following incorrect presumptions: (1) that the Karakhanid Old Turkic of Makhmud al-Kashgari is equal to all of the Turkic languages (in other words, that Middle Turkic = late Proto-Turkic); (2) that Orkhon Old Turkic has been correctly and uncontroversially reconstructed from the script and it reflects /y-/, even though we hardly know the actual pronunciation in the Orkhon inscriptions; (3) that the high level of differentiation among different Turkic subgroups can be ignored, including the evidence for the maximum differencies in the Siberian languages and Chuvash — in this approach the evidence from the Kimak-Kypchak-Tatar languages, for instance, may play the same role as the evidence from Sakha, and indeed this was the situation in Russian and European Turkology until the beginning of the 20th century, when most Turkic languages were officially viewed as merely dialects of each other. Even in SIGTY, Chuvash is still unreasonably included into the mainstream Turkic languages, at least as far as the phonological reconstructions are concerned.

As a final touch, we can describe a phonological calculation based on the above-postulated formula used in the reconstruction of the S-phoneme:

1/2 Proto-Chuvash /s'-/ + 1/2 [1/3 Proto-Yakutic /s-/ + 1/3 (1/2 (1/2 Proto-Altay-Sayan /ch'-/ + 1/2 (1/2 Proto-Kimak-Kypchak /j'-/ + 1/2 Proto-Kyrgyz-Kazakh-Chagatai /j-/)) + 1/3 Proto-Oghuz-Orkhon-Karakhanid /y-/)] =

1/2 Proto-Chuvash /s'-/ + 1/2 [1/3 Proto-Yakutic /s-/ + 1/3 (1/2 Proto-Altay-Sayan /ch'-/ + 1/2 Proto-Great-Steppe /j'-/ ) + 1/3 Proto-Oghuz-Orkhon-Karakhanid /y-/)] =

1/2 Proto-Chuvash /s'-/ + 1/2 [1/3 Proto-Yakutic /s-/ + 1/3 Proto-Central /ch'-/ + 1/3 Proto-Oghuz-Orkhon-Karakhanid /y-/]

It follows from this expression that the original Proto-Bulgaro-Turkic *S-phoneme was most likely similar to a soft palatalized /s'-/ as in modern Chuvash /s'/, Russian /sh'/ or Japanese , hence for instance */s'etti/ "seven" as in the Indo-European *septem, not *yetti, as it perhaps follows from Turkish, Azeri, Uzbek, Karakhanid and other widespread Turkic languages.

At a later stage, the phoneme began to change into a soft palatalized unvoiced /ch'/ or voiced /j'/ after the separation of Proto-Yakutic, whereas the mutation to /y-/ was a relatively recent innovative phenomenon typical only of the sourthern branch of Turkic languages.

- Collecting factual material

Comprehensive research in Turkology was often hindered by the large number of languages and dialects (somewhere over 50 when all the major dialects are counted) and the lack of detailed grammars and dictionaries for some of them. In many cases, the language descriptions were composed only after the 1920's or even after World War II.

As a result, most of the 19th century's Turkological classifications had originally been built upon phonological criteria alone. The grammatical features were slowly added in in the course of the 20th century, whereas detailed lexcicostatistical and glottochronological analysis seems to be the thing of the recent past that appeared mostly in the 1990's.

In the present chapter, we will briefly summarize the essential lexical, grammatical and phonological evidence collected as the basis for further examination in the next chapters.

2.1 An overview of the lexicostatistical research in Turkic languages

In the beginning of the 21st century, several authors attempted to conduct some purely statistical studies of the Turkic languages, in most cases without any manual analysis of grammar or vocabulary.

Starostin (1991)

Sergey Starostin [STAH-res-tin] included some very detailed 110-word Swadesh-Yakhontov wordlists for 21 Turkic language in his book [Altajskaja problema i proiskhozhdenije japonskogo jazyka (The Altaic Problem and the Origins of the Japanese language), Moscow (1991)]. These lists were apparently later reintegrated into the Starling database.

Dyachok (2001)

A work conducted by M. Dyachok [pronounced: d-yah-CHOK] was published online as brief preliminary notes. In the introduction to his concise article, the author reminds the reader of the old geography-based classification by Samoylovich [sah-moy-LAW-vich] (1922), which had similar results, and then performs the lexicostatistical and glottochronological analysis of the 13 major Turkic languages. As a result, the Turkic languages were subdivided roughly into merely four basic subgroups (1) Bulgaric (2) Yakut, (3) Tuvan, (4) Western (= any other), which conforms to the idea that their area of maximum diversification was located somewhere in the east.

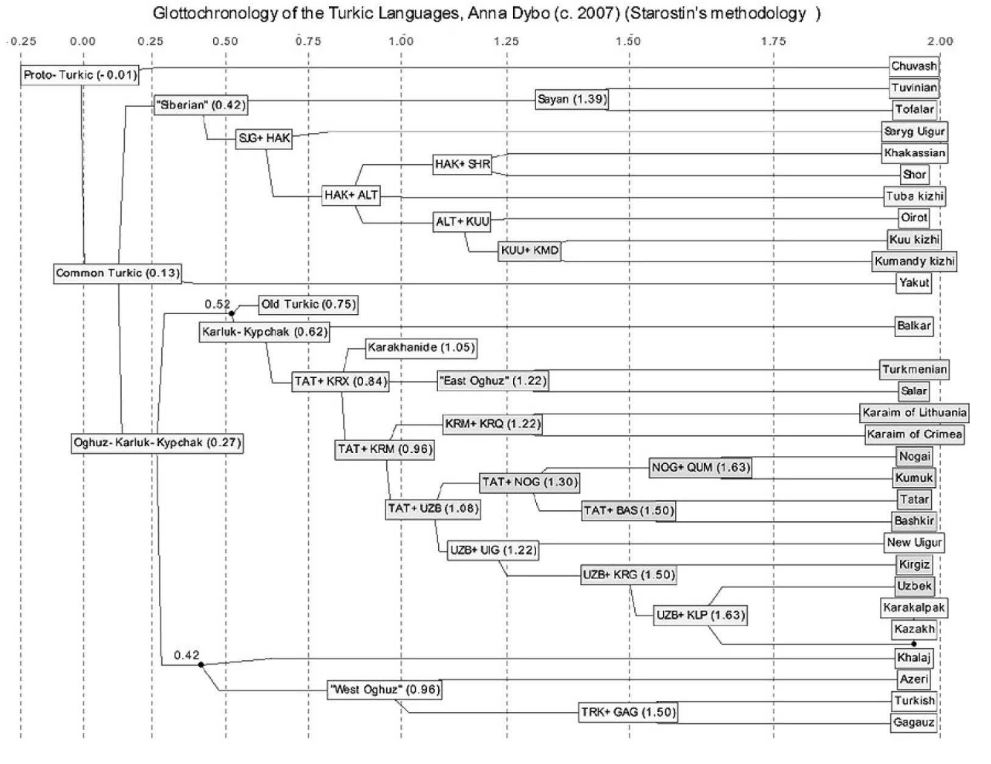

Dybo (2002, 2007)

The study by Anna Dybo [AHN-nah deh-BAW] was first published in 2001 as part of the articles collected in SIGTY [( Sravnitelnaja grammatika tyurkskikh jazykov (The Comparative Grammar of the Turkic languages)]. Then, it was republished in 2007 in a separate book [Anna Dybo, Lingvisticheskije kontakty rannikh tyurkov. Leksicheskij fond. (The Linguistic Contacts of the Early Turks: the Lexical Fund), Moscow (2007)].

The study cites Dyachok as a recent lexicostatistical publication and then briefly describes its own methodology, "All the languages, for which the 100-Swadesh wordlists could be collected from written sources, were included into our investigation. The 100-word Yakhontov-Starostin wordlists were employed, taken that they allow better accuracy [= than the classical Swadish-100]; they were processed according to Starostin's methodology by excluding the recognizable borrowings and employing the STARLING program [...]"

As a result, the following dendrogram was obtained:

Dybo, Anna, The Chronology of the Turkic languages and the Linguistic Contacts of the Early Turks (2006)

There also exists a second version of this dendrogram that drastically differs from the first one, because of some kind of unexplained procedure that was applied to synonyms. This is slightly confusing and may result in the underestimation of the dendrogram's significance, however the first tree above (with the synonyms included) partly matches the outcome obtained in other investigations. Apart from such unconventional points as (1) the splitting of Turkmen and Turkish between two different taxa, (2) the positions of Yugur and Salar, (3) the slightly misplaced Kazakh (which cannot be directly related to Uzbek) and Uzbek position (which is known historically to be related to Uyghur), it is in fact in relatively good correspondence with other studies. However, the glottochronological part based on Starostin's formulas should be taken with a grain of salt.

It should also be noted that the use of shorter 110-word lists results in lower statistical robustness than in the current series of publications that uses larger 215-word lists. Nevertheless, this work has an advantage of representing a greater set of languages, especially those of the Altay-Sayan area, which are normally underestimated or omitted in other studies.

ASJP (2009)

Another example of a phonostatistical research that merits mentioning is the automated dendrogram built by the Automated Similarity Judgment Program for most languages of the world. Here's a preliminary an simplified first-approximation phonostatistical dendrogram of Turkic languages (gif) from 04/2009.

The study was based on a simple 40-word list. Many branches seem to be mispositioned, apparently due to certain limitations of the ASJP's initial approach, however you can see the early separation of Proto-Chuvash, then Proto-Oghuz, and then the rest of the languages, which is partly consistent with the conclusions obtained in the present work and other studies.

Herein (2009, 2012)

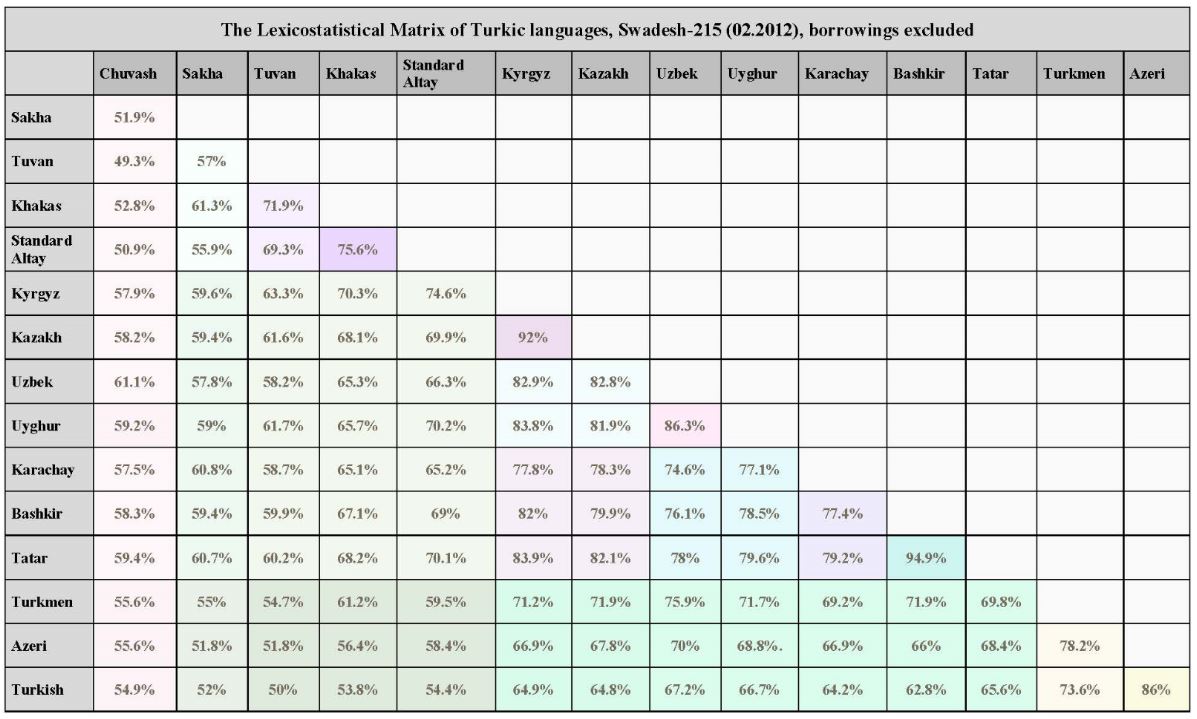

To prepare a lexicostatistical research for this publication, it was decided to use the readily available 200-word Swadesh lists from Wiktionary.org.

After verifying and correcting the available materials, building some new lists for absent languages (such as Khakas, Tuvan, Altai) (2009), composing a php-program to do all the routine calculations, performing some additional meticulous examinations and adding some new lexical material thus expanding the lists to 215 entries (2012), another lexicostatistical study named The Lexicostatistics and Glottochronology of the Turkic languages was finally produced.

It should be noted that the lexicostatistical figures obtained in 2009 and 2012 sometimes differed significantly from each other, because of different approaches used to account for the unavoidable synonymy. The 2009 approach had been much too basic and consequently was significantly enhanced in 2011-12, which included both reexamining the original lists and introducing changes into the program application, so the present version is to be considered more correct.

Most borrowings (Persian, Arabic, Mongolian, Russian, etc) were excluded wherever possible, so only the verified cognates were counted in the final glottochronological section of the study. In the doubtful cases the cognacy was determined according to the [Etymologicheskij slovar chuvashskego jazyka (The etymological Dictionary of Chuvash), by M. Fedotov; volume 1-2, Cheboksary (1996)] and sometimes using the [Etymologicheskij slovar tyurkskikh jazykov (The etymological Dictionary of the Turkic languages), E. V. Sevortyan, Vol. 1-7, Moscow (1974-2003)].

The lexical lists presently differ from the Wiktionary.org materials and are available online as a Word document

As the final outcome of the study, several lexicostatistical matrices of Turkic languages were built.

Considering that an accurate analysis is supposed to include phonological, grammatical, historical and other non-lexical evidence, the lexicostatistical data alone are most likely insufficient to build a complete dendrogram of the Turkic languages at this point,

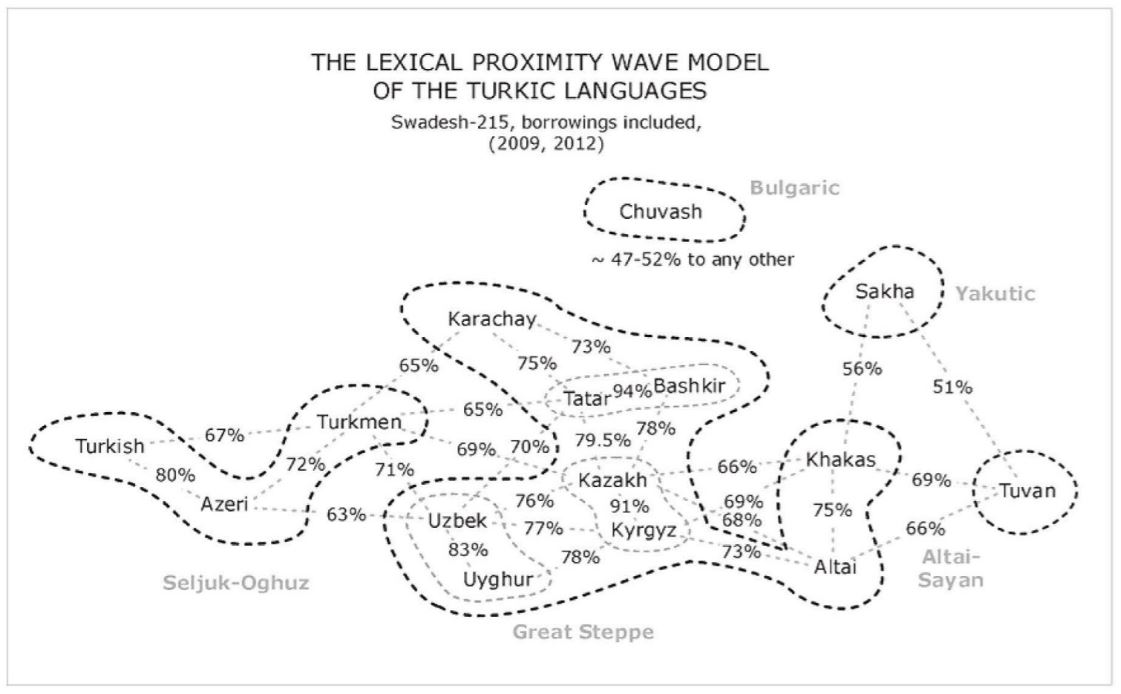

However, we can use the values in the table to build a wave model of Turkic languages that would reflect the mutual language intelligibility through the calculated relationships in the basic vocabulary. The wave model should be based on the borrowings-included matrix, because it is supposed to represent the mutual intelligibility as it is, without any exclusions, for this reason you may notice some small discrepancy in percentages with the table above.

The wave model of the Turkic languages with borrowings included from

[The Lexicostatistics and Glottochronology of the Turkic languages (2009-2012)]